Tocommemorate the bicentennial of Charles Darwin’s birth, London’s Natural History Museum (NHM) commissioned its first permanent installation of contemporary art. In 2009, Tania Kovats was selected from the shortlist of 10 contenders. The artist had long been fascinated with the links between landscape and culture, and often took a scientific approach to her work, fascinated by the way scientists document their experiments.

Two years earlier, she had undertaken a project clearly linked to natural history and conservation. Meadow involved moving a living wildflower meadow on a barge from Bristol to London. This echoed a project planned by Robert Smithson to place ecosystems, including mature trees, on barges in New York’s Hudson River. Although envisaged in 1970, around the time he was completing Spiral Jetty. It was eventually realised, posthumously, in 2005 under the supervision of his wife, the artist Nancy Holt, as Floating Island to Travel Around the Island of Manhattan.

Kovats’ Meadow resonated with the rewilding initiative that was gaining momentum and, by utilising the canal network, commented upon England’s industrial heritage. Meadow drew attention to the relics of the Industrial Revolution when canals carried coal to fire the furnaces of steam-powered manufacture and were the distribution arteries for both the raw materials and goods produced. A reminder that although the Industrial Revolution had powered us into the modern world we know, it was the beginning of our exploitation of fossil fuels that wreaked such environmental damage and for which we must now make amends.

By 2009, Shoreditch Council began adding greenery to canal sidings and islands, also investigating the viability of recycling old barges as floating gardens and meadows. It was a green trend that would grow along the branches of the British canal system. Soon after, the narrowboat community of London began staging occasional festivals which showed-off the roof gardens on their barges, literally bringing nature into the heart of the city and inviting the public aboard to enjoy. This is what Joseph Beuys might have called ‘social sculpture’ — extending an artwork by stimulating community engagement and dissemination.

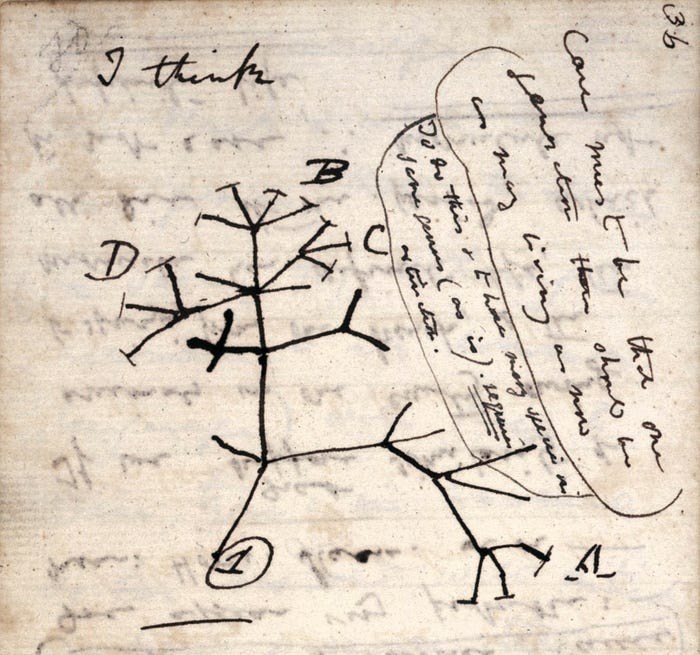

‘…the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever branching and beautiful ramifications…’ — Charles Darwin, 1859

For the Natural History Museum project, Kovats was drawn to the iconic page in one of Darwin’s notebooks from 1837 which first depicted his ‘Tree of Life’ concept. The small page begins with the words I think, and then shows a branching diagram sketched in ink and labelled with some capital letters. It’s as though only this visual expression could capture his initial inspiration and thought process, later explained so eloquently in his book On the Origin of Species… finally published in 1859.

‘I am drawn to those moments in the history of science where those imaginative leaps take place. I’m also interested in the craft of science, the way that scientists prepare experiments, act them out, record them, the drawings and notebooks they use. The thought trails that they make I find really interesting.’ — Tania Kovats

Tania Kovats travelled to South America, exploring the landscape where Charles Darwin had started to develop his theories of evolution during his voyage onboard the HMS Beagle. She joined the 2009 Gulbenkian Galápagos Artists’ Residency Programme, arranged in collaboration with the Charles Darwin Foundation.

Kovats was also informed by the wonderful interior of the Museum itself, decorated with all manner of flora and fauna based on the architectural designs of Alfred Waterhouse, as well as panel paintings of botanical specimens in the ceiling of some galleries. She also found inspiration in the specimens on display, which include Mary Anning’s prehistoric fish fossils, and a cross-section of a giant Sequoia redwood with its rings labelled with historic human timelines to emphasise how long-lived the original tree had been.

Fascinated by this inherent aspect of history that a tree records as it grows, she decided to present a thin longitudinal slice, cross-sectioning the entire height of a 17-metre oak which had been an acorn in the time of the Industrial Revolution. More importantly, it was one that started to grow in 1809, the year of Charles Darwin’s birth. She decided to use the tree in the manner of a large botanical specimen, embedding it into the panelled ceiling of the NHM’s Cadogan Gallery in Central Hall. This was indeed an ambitious project that referenced scientific specimen and grand-scale architecture.

Kovats selected the tree from the managed woodlands of the Longleat Estate, in Wiltshire, where oaks have been grown for floorboards and roofing beams for centuries. A tree, nearing its schedule for felling, was chosen with care so that the shape of the tree would be suitable for the long gallery ceiling and its ‘imposing majesty’ could be preserved in the final installation.

The tree-felling operation, also involving digging-out the huge root ball, was conducted carefully and approached scientifically. In the process samples of the creatures living on the tree — millipedes, spiders, slugs, ladybirds, earwigs, to name just a few — were recorded in the Natural History Museum collection. A biodiversity pond was created in the hollow left by the tree. Its many young saplings were all around, waiting to grow now they would be no longer shaded by its broad canopy and an additional 200 new trees were planted to be designated ‘Darwin’s Wood’, a living monument and record of his theory. The negative space and woodland planting are also part of the art work, creating a dialogue of distance between the tree’s origin and the gallery where it is displayed.

The trunk, branches, and roots were carefully sliced into cross-sections and dried, so that Kovats could select the most interesting and beautiful layers to use. These were fixed onto lightweight aluminium panels, sanded and waxed to show their colour and intricate grain.

I recall visiting the museum and admiring the ceiling as a biological specimen, not realising it was an art installation at the time. It suggested the huge life-size model of a blue whale suspended in another hall of the Museum. The tree’s beautiful, sinuous shape seemed to reach beyond the gallery. Kovats had wanted this effect, inviting us to imagine what lay beyond and suggesting the fairy-tale aspect of trees and forests, linking the land with human imagination.

A limited cross-section of a selection of branches was also taken and dried. These smaller sections were collectively called Branch and one was gifted to each of the countries visited by the HMS Beagle on its historic voyage, as a celebration of Darwin’s life and work. This extended that dialogue of distance yet further, explicitly linking the work with the historic five-year, round the world voyage.

‘The tree is a model of connectivity, ancestry and genealogy. In Darwin’s diagram he was mapping out the future of biological knowledge and set in motion an investigation that we are still engaged with today...’ — Tania Kovats

Since this installation, arts and science have continued to collaborate closely to commemorate milestones in scientific history; also to communicate the importance of the environment and the effects of climate change. Tanya Kovats is now Professor of Drawing at Bath Spa University, currently working on a project connecting drawing with mindfulness, and the Natural History Museum is shortlisted for the Art Fund’s Museum of the Year 2023 prize, the biggest Museum prize in the world and the UK’s largest arts award.